Vick Quezada: navigating the post-apocalyptic settler world

‘A dominant world of erotic power and joy’ is what interdisciplinary artist Vick Quezada (they/them) envisions in their work. They view histories and practices that existed long before western structures became dominant in our culture, particularly Indigenous Aztec and Nahuatl religious gender formations, and combine these with modern queer narratives to form a center of inspiration from which they work. Their multifaceted work embodies a concern with our current environmental crisis, viewed through a two-spirit Aztec lens that criticizes the way western capitalism and binary thinking have contributed and continues to contribute to the state we’re in.

An article based on the conversation I had with Vick will be published in the upcoming publication DISPOSITIVE: Where do we go from here?, in collaboration with the fellows of TASAWAR Curatorial Studios.

Vick Quezada, Female to Fungi (FtF), 2020, digital photograph.

What stands out about your work and the way you handle the histories you look back on is that the emphasis often lies on instances of beauty and pleasure, rather than mostly focusing on where things went wrong.

Yes, absolutely, that has a lot to do with queer temporality. My ‘looking back at time’ is an active practice. You can liken it to relationships, specifically romantic relationships. A lot of times, we look at the linearity of romantic relationships and look back on them afterward wondering what went wrong so that we can take the lessons from that into the next relationship. I look at civilizations in that way, particularly Aztec and Mexica Indigenous history, and I place them along the lines of the current cultural formation we’re in. It’s not that I think there are perfect ways of governance or being, but I do think that there are ways of governing that are more ethical.

In Aztec spiritual practices, two-spirit people were actually celebrated. You can see it within their deities! And before European colonizers arrived, Aztec Indigenous people did not have a concept of sin. Their concept of morality was ‘everything in moderation’. So there was no good or bad, and therefore no judgement for things like homosexuality or gender variance. But now we have these binaries not only categorizing gender and sexuality but also culture. So I look at the conditions that formulated the way we currently live, and I feel like I often go back to a trans-feminist Marxist analysis that points to hetero-patriarchy and capitalism. I think capitalism is probably the driving force of how these formations are created, how power is relegated, and how bodies are marked as valuable or invaluable.

I’m hearing a lot of social, cultural, and political challenges you’re addressing, while in the form you’re also drawn to more organic materials and ecological aesthetics, and I get the sense that these are intertwined for you. For example, you’ve said before that you like to work with clay because clay is land and land is political.

If you look at biology and things found in nature, you’ll find a lot of animal and plant species deviate from the arbitrary binary systems we cling to. We try to use binaries to categorize living organisms but they often can’t be categorized. I use a lot of corn because it’s a sacred plant in Mexica culture, the Aztecs worship corn like a deity, like a progenitor for Aztec life. It’s almost uncanny, but there are two gods that represented corn, Chicomecoatl and Cinteotl, a woman and a man. And later, scientists discovered that corn is a monoecious plant, which means it has two genders. So these are intersections that inspire me to create. It’s like a testament to how the structures of society are all fabricated. They’re created to subject people and establish a certain type of order. Indigenous people are spiritually very connected to nature, and they believe land can not be owned by a person. There’s an honoring of plant life and animal life in Indigenous culture, an honoring of the entire cosmos. They believe humans are stewards to the land, which is very anti-capitalist.

Vick Quezada, Life at the Precambrian Beach, 2019. Photograph from Seed/Unseed performance taken by Chuck Bayliss.

Your performance ‘Seed/Unseed’ is a good example of how you use corn as a tool to explore these structures and histories, can you tell me about that?

For that performance I went back to my hometown of El Paso, Texas, which is right on the Mexican border. Along the border, there are these Spanish colonial missions that were built when the Spaniards were trying to expand their ownership of the land in that area. These missions were like forts, and there were all these colonial soldiers in the area to indoctrinate some of the local Indigenous people there and change their religious practices. So I was thinking about these missions and their function, which is to assimilate and discipline Indigenous peoples into loyal subjects to the crown. So a lot of them left their Indigenous practices and conformed to Catholicism. For the performance itself, I took these sacred corn seeds to reconcile this history and the land. I seeded the ground with a plush pink corn seeder, which was inspired by the Aztec god Ozomatli. Ozomatli was a companion of the flower prince, who is another two-spirit entity in Aztec religion. So I walked the path along these three missions, seeding the ground with this little pink monkey as a way to reconcile the land with these colonial border histories.

As an artist who is concerned with land and ecology, how do you view our current state when it comes to things like climate change and the pandemic?

I was looking at a chart the other day that was measuring carbon levels in the atmosphere over a time frame covering pre-colonization, post-colonization, and the contemporary time. And right around the time colonization began in the Americas, when the Spaniards arrived around the 1500s, the chart dipped. Scientists have tried to figure out what happened there, and it’s said that it’s the result of mass extinction. They estimated that there were around 90% of the Indigenous population living at this time, amounting to around 55 million people, were wiped out. So the carbon levels dropped because there were fewer people to leave their carbon footprint. And after this dip, the carbon levels kept rising to the critical point where we are now. To me, that’s such an important example of how these problems are intertwined. We are at a point of no return when it comes to climate change, and I am very critical of the ways that settler colonialism, capitalism, and hetero-patriarchy have contributed and continue to contribute to this situation.

We’re living in the age of the Anthropocene, and when scientists talk about the Anthropocene, they refer to humans as a collective, that the entire human race pushed us over the edge. But it’s not all humans, that’s something we need to realize. It’s capitalism. We need to understand who is causing this and for what purpose.

One of your artworks that I wanted to talk about, that kind of relates to both this dip in carbon emissions as well as the current pandemic, is ‘500 Years a Plague’. I have also been increasingly aware of how the AIDS epidemic ruptured the queer community, now that the entire world is in a similar situation. So, again, there seem to be a lot of parallels there.

When I made that piece I was thinking about these parallels, and Europeans coming to the Americas to spread smallpox and other plagues among Indigenous communities. It’s about the way biological warfare on bodies was a factor in the reduction of Indigenous people, and how that same phenomenon is occurring now, hundreds of years later. Capitalism and western beliefs have created the conditions that are happening right now. There are these necropolitics of value, we’re thinking about who gets to live and who dies. An example is how Trump got sick with COVID, and he was given a cutting-edge treatment that increased his white blood cell count. This treatment isn’t given to working-class people, most often people of color, in the fast-food industry or retail, even though they have been the front-line workers during this pandemic. Some of these people don’t even have healthcare. It’s this mentality of bodies that aren’t valued, or that aren’t needed enough to keep alive. So I put these factors in the piece along with these visuals from my own personal narrative, and the combination of them became like a marker of death and life. There’s dark humor installed in it to show the absurdity of capitalism and the relegation of death.

Vick Quezada, 500 years a Plague, 2021, ceramics, land stakes, fence, lights, roof panel, Euphorgia Tirucalli.

Does it have the function of a tombstone?

Sure, I made this around the time when monuments all over the world were being toppled and destroyed. We see and hear these things in daily life, both good and bad, and the things that we as artists or producers make are not in a vacuum. So the monuments definitely impacted what I was thinking about. I think I like to think of the piece as a maquette, and in a way monuments are maquettes as well. The way they’re almost sitting in for the real thing.

I’d also like to talk about your rasquache practice, and the function of that in your work.

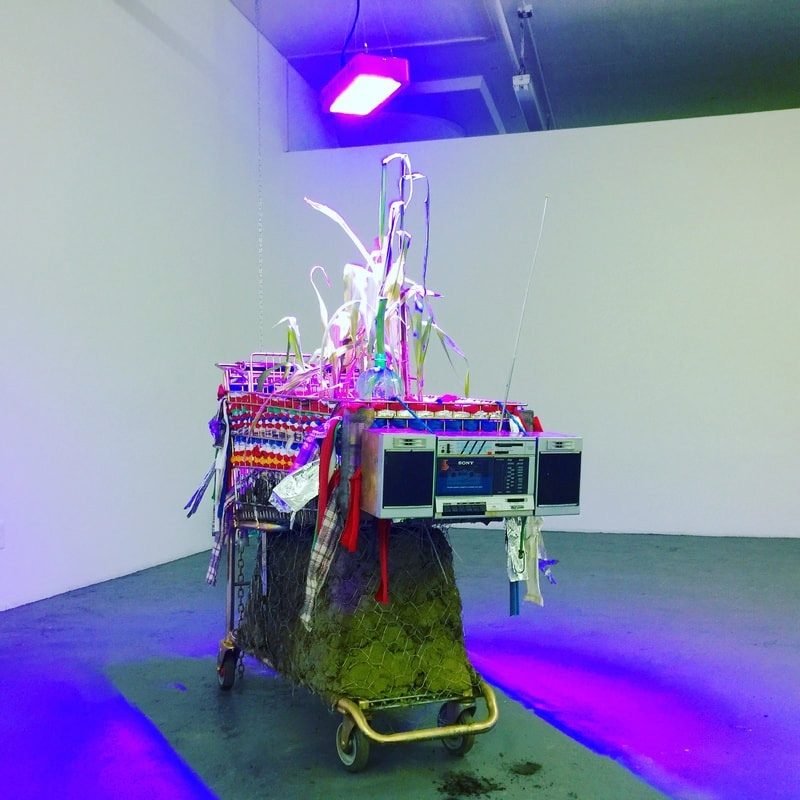

I have a lot to say about that! Rasquache art is the use of found objects and turning them into something practical and functional. To me, it’s not really just art, although that is what it has become. But it is a practice that I learned as a child, something my father and his father practiced. My dad would source material from the side of the road or that he was gifted, and he would create these building structures from it. It’s a different way of using these found objects that weren’t intended for the structures he created but still making it work. This practice is out of financial motivation, to sustain oneself, and I became immersed into it from a very early age just by living my daily life. So it naturally happened in my work. I even tried to move away from it when I went to art school, but it didn’t feel like I was making art that was speaking from my experience. At one point I had a shopping cart in my studio that I was just using to transport stuff back and forth. And suddenly I wondered what would happen if I made a garden in that shopping cart. So I just embraced that thought and continued to work from it. I’d say 85% to 90% of my art is Rasquache.

Vick Quezada, Cart No.1, 2016, shopping cart, maize, t-shirts, boombox, mixed dimensions.

I was watching this show called Station 11. It’s about the apocalypse, and there are so many movies about the apocalypse, but this one struck a chord because the characters were wearing these DIY costumes that you often see in post-apocalyptic movies. They looked so futuristic and magical and wonderful, it was mindblowing. In a lot of other post-apocalyptic movies the costumes are these armored, war-like ensembles that are just a little unapproachable, but these ones almost had a friendly, queer aesthetic to them, which really reminded me of my work. When people face poverty and destruction, these are the manifestations that come out of that. There’s the post-apocalyptic, settler colonial thought and aesthetic that’s embedded into it, like a survivor narrative. You’re sifting through all this refuge and waste and finding value in it.

As an outsider who doesn’t know about Rasquache might mistake it for having an environmental connotation to it, like upcycling. But does it tie more into your personal and cultural background than that?

That’s a big factor in it, but I also think that growing up in financial insecurity created an awareness of waste. It goes as far as throwing away food, I always think if I can put it outside and let the wildlife eat it, and if it’s not edible for them, then I will dispose it. And this awareness runs very deep in my family. So there’s the financial necessity, but it’s also a cultural thing to be very aware of how you’re moving in the world and using resources.

Do you think it’s a privilege to be concerned with the environment and sustainability, as opposed to resorting to a practice like Rasquache out of financial necessity?

Of course, I think people who are able to eat a gluten free diet or vegan diet that are high quality and expensive is absolutely a privilege. I don’t have a judgement on that type of lifestyle, I think everyone should have the healthiest lifestyle they can afford, but there’s also inequality in that not everyone has access to that type of stuff. Or even the knowledge of what’s good or bad for your body. And I think the way I source my materials is also a response to these social and class structures.

You often speak of an ‘alternate world of erotic power and joy outside the dominant narratives’. What does that world look like to you? Do you think it can be a solution to the challenges you address in your work?

I do. Although I don’t think we can ever really do away with some of these unjust systems that are in place. But if we really start thinking about people who are relegated as invaluable, or how we exploit natural resources, and if we started caring from the least common denominator, then I think it would trickle up. Starting with trans and black life, for example, I think if we started caring about nature and the exploitative structures we have in place, that would transcend into all other aspects of life. There’s always an awareness that the work isn’t gonna change the world, but it adds to the dialogue. It’s about care and value.